Carbon in Vesta's craters

Large impacts of asteroids may have transferred carbonaceous material to the protoplanet and inner solar system

The protoplanet Vesta has been witness to an eventful past: images taken by the framing camera onboard NASA's space probe Dawn show two enormous craters in the southern hemisphere. The images were obtained during Dawn's year-long visit to Vesta that ended in September 2012. These huge impacts not only altered Vesta's shape, but also its surface composition. Scientists under the lead of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Katlenburg-Lindau in Germany have shown that impacting small asteroids delivered dark, carbonaceous material to the protoplanet. In the early days of our solar system, similar events may have provided the inner planets such as Earth with carbon, an essential building block for organic molecules.

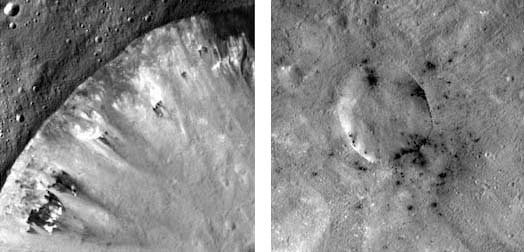

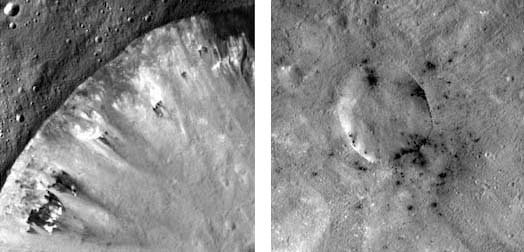

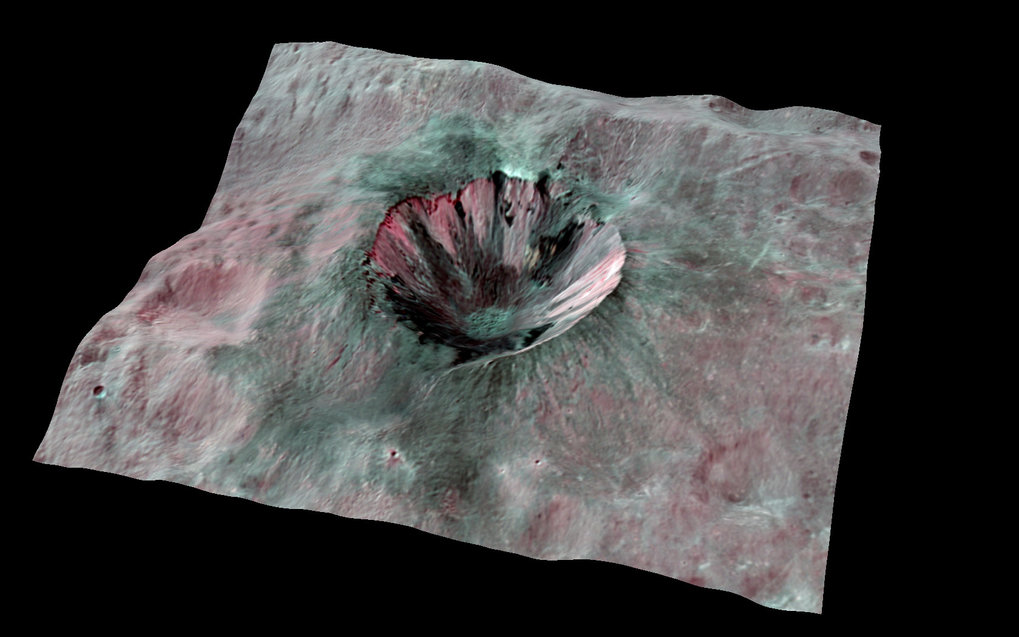

Vesta is remarkable in many respects. With a diameter of approximately 530 kilometres, Vesta is the one of the few protoplanets in our solar system still intact today. Like other protoplanets, Vesta underwent complete melting approximately 4.5 billion years ago. However, most of the volcanic activity on Vesta is thought to have ceased within a few million years making it a time capsule from the early solar system. Dawn observations of Vesta have shown a surface with diverse brightness variations and surface composition. There is bright material on Vesta that is as white as snow and dark material on Vesta as black as coal.

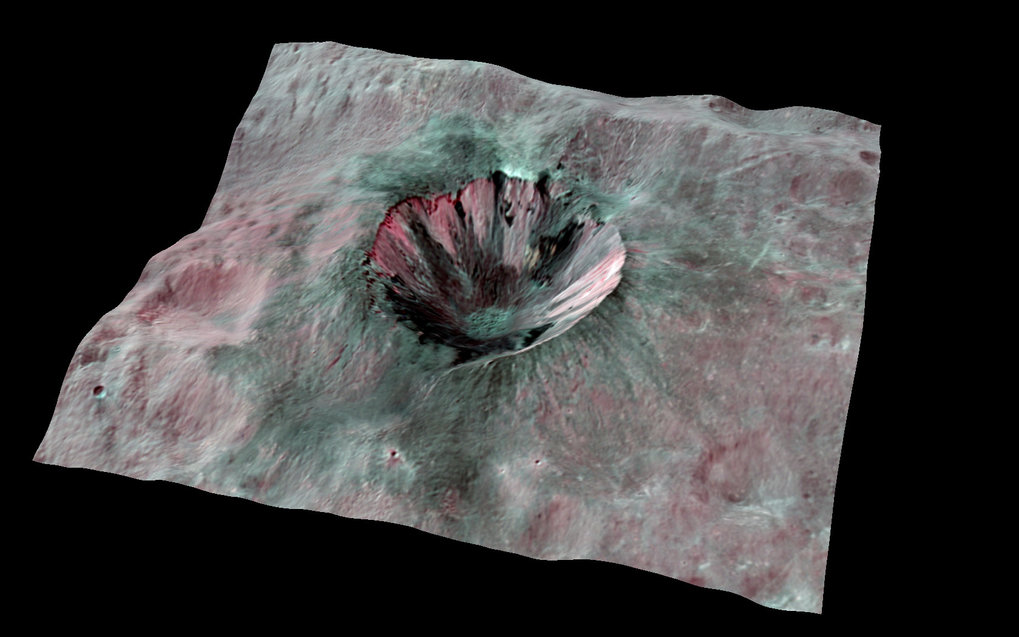

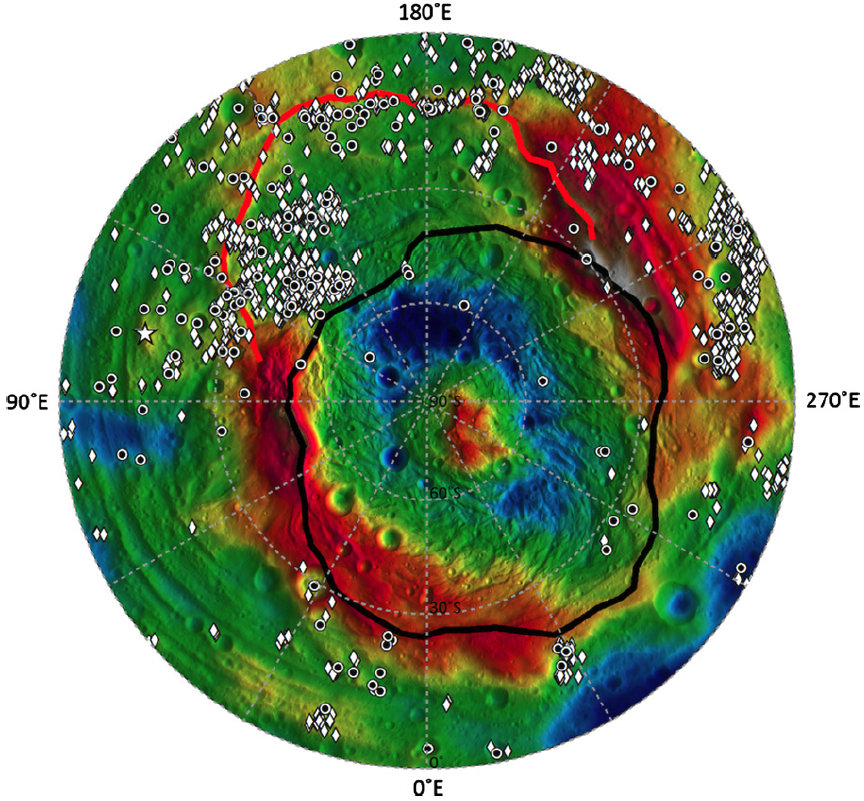

The enigmatic dark material holds the key to understanding the impact environment around Vesta early in its evolution. Research led by scientists at the Max Planck Institute in Katlenburg-Lindau has shown that this dark material is not native to Vesta but was delivered by impacting asteroids. “The evidence suggests that the dark material on Vesta is rich in carbonaceous material and was brought there by collisions with smaller asteroids,” explains. Vishnu Reddy from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research and the University of North Dakota, the lead author of the paper. In the journal Icarus, he and his colleagues now present the most comprehensive analysis of this material so far. Compositional analysis, mapping, and modelling of dark material distribution on Vesta suggest that it was delivered during the formation of giant impact basins on Vesta.

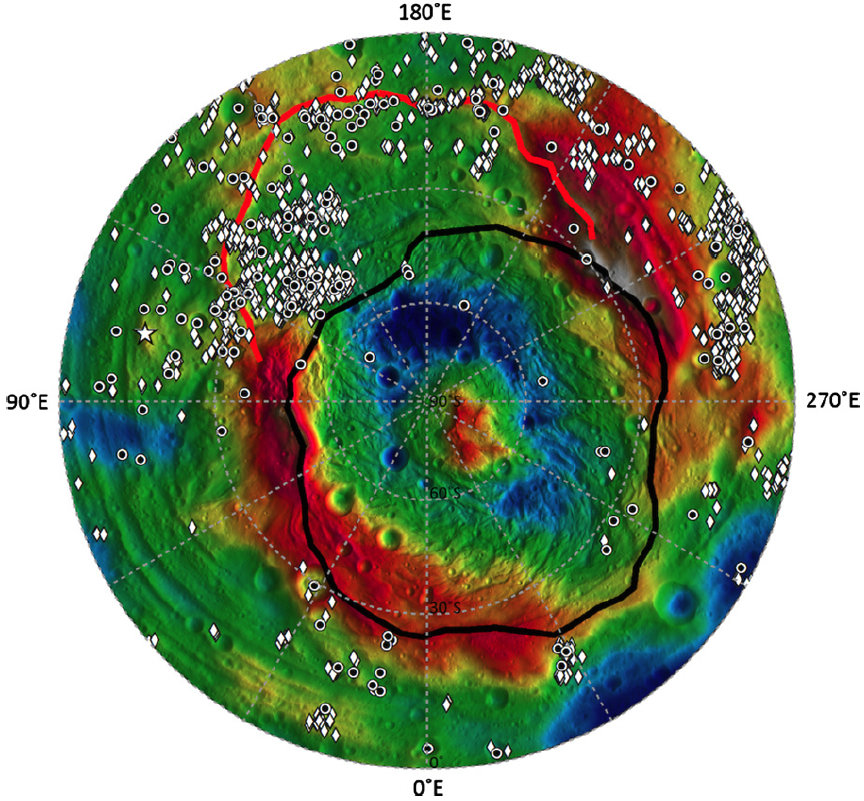

The dark material arrived with the first impact on the protoplanet

“First, we created a map showing the distribution of dark material on Vesta using the framing camera data and found something remarkable,” explains Lucille Le Corre from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research one of the lead authors of the study. Dark material was preferentially spread around the edges of the giant impact basins in the southern hemisphere of Vesta suggesting a link to one of the two large impact basins. A closer examination showed that the dark material was most probably delivered during the formation of the older Veneneia basin when a slow impacting asteroid collided with Vesta. Dark material from this two to three billion year old basin was covered up by the impact that subsequently created the Rheasilvia basin. “We believe that the Veneneia basin was created by the first of two impacts two to three billion years ago,” says Reddy. In fact, impact modelling presented in the paper reproduces the distribution of dark material from such a low velocity impact.

HED meteorites are fragments of Vesta

Evidence for dark material is also found in the HED meteorites that come from Vesta. Some of the meteorites show dark inclusions that are carbon-rich. Colour spectra of dark material on Vesta are identical to these carbon-rich inclusions in HED meteorites. The link between dark material on Vesta and dark clasts in HED meteorites provides us with direct evidence that these meteorites are indeed from Vesta. “Our analysis of the dark material on Vesta and comparisons with laboratory studies of HED meteorites for the first time proves directly that these meteorites are fragments from Vesta”, says Le Corre.

“The aim of our efforts was not only to reconstruct Vesta's history, but also to understand the conditions in the early solar system,” says Holger Sierks, co-investigator of the Dawn mission at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research.

The Dawn mission was launched approximately five years ago and entered orbit around Vesta on July 16th, 2011. In 2015, Dawn will arrive at its second destination, the dwarf planet Ceres, that like Vesta orbits the Sun between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter within the so-called asteroid belt. The Dawn mission to Vesta and Ceres is managed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington. The University of California, Los Angeles, is responsible for overall Dawn mission science. The Dawn framing cameras have been developed and built under the leadership of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, Katlenburg-Lindau, Germany, with significant contributions by DLR German Aerospace Center, Institute of Planetary Research, Berlin, and in coordination with the Institute of Computer and Communication Network Engineering, Braunschweig. The Framing Camera project is funded by the Max Planck Society, DLR, and NASA/JPL.