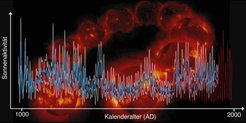

Solar activity reconstructed over a millennium

Ancient tree slices and an improved C14 method provide a unique glimpse into our star's past.

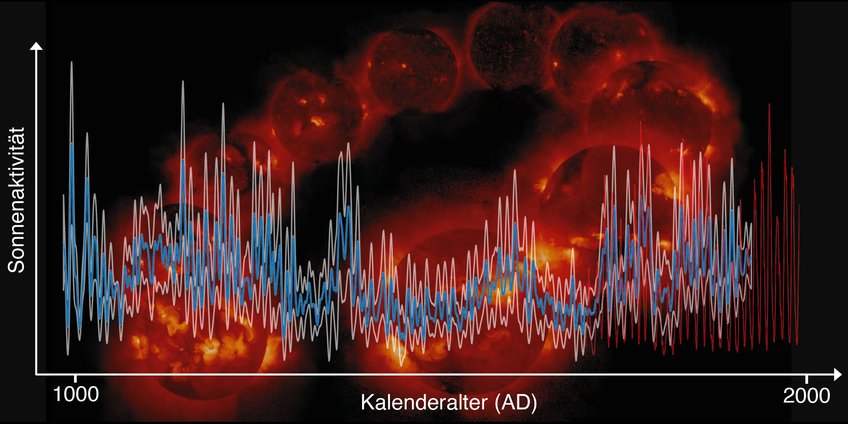

An international research team, including scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany, has reconstructed solar activity up to the year 969 without gaps and with a high temporal resolution of only one year from measurements of radioactive carbon in tree rings. The data, which the team led by ETH Zurich recently published in the journal Nature Geoscience, not only impressively confirm the Sun’s known, eleven-year activity cycle. They also show that in long-lasting phases of low solar activity, the fluctuations of solar activity are smaller than usual. In addition, the researchers discovered that the Sun ejected particularly high-energy particles into space not only in 993 - as already known - but also in 1052 and 1279. The results help researchers to better understand solar dynamics and allow more precise dating of organic materials using the C14 method.

The Sun’s activity can only be observed indirectly. Sunspots, for instance, can give important clues: the more sunspots are visible on the solar surface, the more active is our central star deep inside. Even though sunspots have been known since antiquity, they have only been documented in detail since the invention of the telescope around 400 years ago. Thanks to that, we now know that the number of spots varies in regular eleven-year cycles and that, moreover, there are long-lasting periods of strong and weak solar activity, which is also reflected in the climate on Earth.

How solar activity developed before the start of systematic records, is by far more difficult to reconstruct. An international research team led by ETH Zurich, which included MPS and Lund University in Sweden, has now traced back the Sun’s eleven-year cycle all the way to the year 969 using measurements of the concentration of radioactive carbon in tree rings. At the same time, the researchers have thus created an important database for more precise age determination using the C14 method.

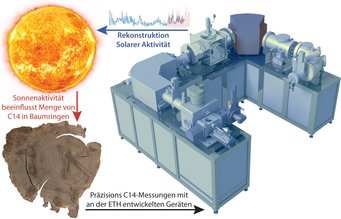

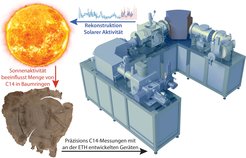

To reconstruct solar activity over a millennium with an extremely good time resolution of just one year, the researchers used tree-ring archives from England and Switzerland. In those tree rings, whose ages can be precisely determined by counting the rings, there is a tiny fraction of radioactive carbon C14, with only one out of every 1000 billion atoms being radioactive. From the known half-life of the C14 isotope – around 5700 years – one can then deduce the concentration of radioactive carbon present in the atmosphere when the growth ring was formed. As radioactive carbon is mainly produced by cosmic particles, which in turn are kept away from the Earth to a greater or lesser extent by the solar magnetic field – the more active the Sun, the better it shields the Earth – it is possible to deduce solar activity from a change in the concentration of C14 in the atmosphere.

Precise measurements of a change in that already very small concentration, however, resemble the search for a grain of dust on a needle in a huge haystack. “The only measurements of that kind were made in the 80’s and 90’s”, says Lukas Wacker of the Laboratory of Ion Beam Physics at ETH, “but only for the last 400 years and using the extremely laborious counting method”. In that method, radioactive decay events of C14 in a sample are directly counted using a Geiger counter, which requires a relatively large amount of material and, owing to the long half-life of C14, even more time. “Using modern accelerator mass spectrometry we were now able to measure the C14 concentration to within 0.1 percent in just a few hours with tree-ring samples that were a thousand times smaller”, adds PhD student Nicolas Brehm, who was responsible for those analyses.

In accelerator mass spectrometry, C14 and C12 atoms (the “normal”, non-radioactive carbon; C14, by contrast, contains two additional neutrons in its nucleus) of the tree material are first electrically charged and then accelerated by an electric potential of several thousand volts, after which they are sent through a magnetic field. In that magnetic field the two carbon isotopes, which have different masses, are deflected to different degrees and can thus be counted separately. To eventually obtain the desired information on solar activity from that raw data, the researchers have to perform some intricate statistical analysis on it and further process the results using computer models.

This procedure enabled the researchers to seamlessly reconstruct solar activity from 969 to 1933. From that reconstruction they could confirm the regularity of the eleven-year cycle as well as the fact that the amplitude of that cycle (by how much the solar activity goes up and down) is also smaller during long-lasting solar minima. "Knowing our star's past as precisely as possible and over as long a period as possible not only helps us better understand the internal dynamics of our star. It also allows us to better estimate how the Sun might behave in the future," says Sami Solanki of MPS.

Thus, the measurement results also allowed a confirmation of the solar energetic proton event of 993. In such an event, highly accelerated protons that reach the Earth during a solar flare cause a slight overproduction of C14. Moreover, the research team also found evidence of two further, as yet unknown events in 1052 and 1279. This could indicate that such events – which can severely disturb electronic circuits on Earth and in satellites – happen more frequently than previously thought.

As tree ring archives exist for the past 14000 years, in the near future the researchers want to use their method to determine the yearly C14 concentrations all the way back to the end of the last ice age. As a kind of “extra”, the data in the new study can be used for dating organic material much more precisely using the C14 method and have already been included in the latest edition of the internationally recognized radio carbon calibration curves.