Sun and Heliosphere

The Sun - the gaseous giant

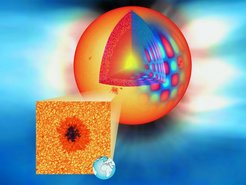

A cutaway drawing of the Sun showing its oscillations (right) from which a detailed picture of the solar interior has been deduced. The blow-up reveals a sunspot produced by the Sun’s magnetic field. The Earth is shown to scale. The Sun’s hot and extended corona is visible in the background.

The Sun is a large ball of gas, 1.4 million kilometer across, consisting primarily of hydrogen and helium, and taking up 99.8 percent of the mass of the solar system. At its center the temperature is 15 million degrees Celsius, hot enough to force hydrogen nuclei to combine to form helium. The energy that is released by this process is transported by radiation and gas currents (convection) to the visible surface of the Sun, where the temperature is 6000 degrees, and is then radiated out into space.

Spectacular coronal mass ejection (CME) observed with the LASCO instrument on board the SOHO spacecraft. Giant gaseous clouds are ejected at speeds of up to seven million kilometers per hour and can result in strong magnetic disturbances on Earth.

The gas currents are thought to generate magnetic fields in the interior of the Sun, causing dark spots and other features to appear on the surface. In the very extended corona, which can be observed without special equipment only during solar eclipses, the temperature again increases to over a million degrees. The hot gas in the corona remains predominantly bound to the Sun’s magnetic field, as though enclosed inside a cage. However, some of this gas escapes, streaming as the solar wind through interplanetary space with speeds of up to three million kilometers per hour.

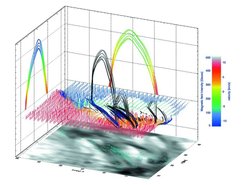

Hot gas is trapped in magnetic loops. This image of such a loop (and its projections) is the result of observational analyses made with the German solar telescope on the Canary Island Tenerife.

Researchers at the Institute study the entire gamut of the Sun’s dynamic and often spectacular processes from the solar interior to the external heliosphere. The main focus of the research is the magnetic field, which plays a decisive role in these processes. Answers to the most basic questions are sought: How is the magnetic field generated? Why does it vary in an eleven-year cycle? How does the Sun’s magnetic field hold the various layers of the solar atmosphere together? How is the corona heated to several million degrees?

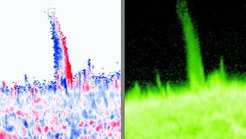

A "solar tornado": The spicule at the solar limb, observed with the UV spectrometer SUMER on SOHO, consists of gas at a temperature of 230 000 degrees that has been ejected by the Sun. The Doppler shift of the light reveals a rotation speed of 50 000 kilometers per hour (right).

New fundamental knowledge about the Sun has been obtained with instruments (co-)developed by the Institute on board the space probes SOHO and STEREO. The measurements from the UV spectrometer SUMER on SOHO have led to the recognition of the decisive role of the magnetic field in dynamic processes, while STEREO allowed for the first time 3D observations of the Sun and the inner heliosphere.

The Sun - a life-giving star

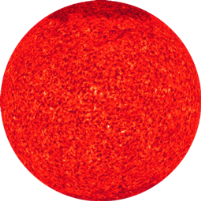

The Sun seen in an ultraviolet emission line of neutral Helium, which is formed at temperatures around 20 000 Kelvin. The dark region at the polar cap - the coronal hole - is the source of the fast solar wind which blows off the Sun into the heliosphere.

The Sun’s radiation brings warmth to the Earth, without which life could not exist. Therefore, any changes on the Sun must be examined for their possible effects on the Earth’s biosphere. Using satellite-borne detectors, researchers have discovered that the total brightness of the Sun varies by about 0.1 percent during the eleven-year magnetic field cycle. Although this variation is very small, it could influence the sensitive equilibrium in the terrestrial climate.

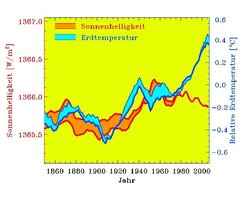

The increase of the atmosphere’s average temperature over the last 150 years (right scale, units relative to the temperature in 1960) shows striking similarities to the rise of the Sun’s irradiance (left scale) only until 1980.

Explosive eruptions on the Sun propel clouds of gas and magnetic fields into space that come into contact with the Earth’s magnetic field. Particularly strong solar storms can penetrate this natural shield, leading to intense auroral activity ("northern lights"), to disruptions in radio transmissions, or even to damage in communication satellites, telephone and power lines. An important research area at the Institute is the investigation of the effects on the Earth resulting from variable activity on the Sun. To this end, the scientists are greatly involved in the NASA project STEREO, in which two satellites are to observe disturbances on the Sun from different directions, allowing predictions of potentially dangerous outbursts.

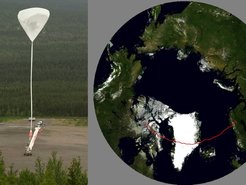

The balloon-borne solar observatory Sunrise, launched from Kiruna in northern Sweden, observed during its second flight in the year 2013 the Sun for more than 5 days from a height of about 35km, before it landed by a parachute in northern Canada.

Current and future projects concentrate on the investigation of the physical causes of these variations on the Sun. The telescope Sunrise, built under leadership of the MPS, observed the structure of the magnetic field in the lower layers of the solar atmosphere with unprecedented resolution during two flights in the years 2009 and 2013, carried by a balloon to a height of about 35 kilometers.

In 2017 the space probe Solar Orbiter is expected to start its journey to the Sun. The probe will approach our central star closer than any other mission before.

The ambitious ESA mission Solar Orbiter, which originates from our Institute’s proposal, plans to launch a spacecraft in 2017, that will approach the Sun at a distance of 28 percent of the Earth-Sun separation, in order to study the magnetic field and its effects in different layers of the solar atmosphere.