Historical Sunspots:

One, two, three … and Counting

In analyzing solar observations from the 19th century, scientists are turning to amateur researchers for help. The project will allow to better understand the history of our star.

In their endeavor to count thousands and thousands of sunspots in historical drawings of the Sun, a joint research project by the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany and the National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) in Italy is looking for assistance from dedicated amateur researchers. Their task is to sift through the almost daily observations of the Sun that astronomer Angelo Secchi and his collaborators recorded in detailed drawings between 1853 and 1878. The collection is one of the most comprehensive data sets on sunspot observations of the 19th century. Such historical data helps to understand how active our star once was - and what it might have in store for us in the future. The project “Sunspot Detectives” is launched today on the citizen science platform Zooniverse.

Counting sunspots

In the second half of the 19th century, a unique collection of observational data of the Sun was created in Rome. For more than three decades, the Jesuit, priest, astronomer and outstanding scientist Angelo Secchi, his collaborators, and assistants regularly peered at our star from the newly built observatory of the Jesuit Roman College on the roof of the church of Sant'Ignazio and transferred their observations into almost daily pencil drawings. With fine lines, they marked the size, shape, and position of all the dark spots they could discern with the help of their telescopes. Since last year, the more than 5,400 drawings, which belong to the Italian National Institute of Astrophysics (INAF) and are stored at the INAF Astronomical Observatory of Rome, have been fully digitized and can now be systematically used for research. Analyzing this huge collection is such a daunting task, that researchers at the MPS and INAF are now turning to the citizen science platform Zooniverse for help.

Solar historical research

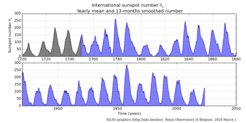

"When we look at the Sun today, we only see a snapshot, a tiny part of its life which has lasted 4.6 billion years so far," explains Dr. Theodosios Chatzistergos from the MPS and INAF associate, who devised the Zooniverse project "Sunspot Detectives". "Only a look back into the history of the Sun can help us to assess of what behavior, in principle, our star is capable - and what we can expect from it in the future," he adds. It is known that the Sun goes through phases of weaker and stronger activity. On a roughly eleven-year activity cycle, significantly longer fluctuations are superimposed. During its active phases, the Sun offers quite a firework: there are frequent eruptions of particles and radiation; the solar wind, the steady stream of charged particles from the Sun, "blows" particularly strongly; the Sun's overall radiation intensity increases; and many dark sunspots - often arranged in groups - cover its surface. In quiet phases, such dark areas appear only rarely or are absent altogether.

Sunspots therefore play a central role in "solar historical research". As they can be observed with simple tools, astronomers have been tracking their number and evolution for more than four centuries. "The number of sunspots is the most important historical measure of solar activity in the modern age as it is the only direct measure of the activity of our star for over the last four centuries," says Chatzistergos. "It allows us to trace the Sun's behavior back over several hundred years and compare it with the current state," he adds.

One Sun, many observers

This makes it all the more important for researchers to have the most precise observational data possible on the number of sunspots. The records that were obtained between 1853 and 1886 at the Roman College and have yet to be systematically analyzed in light of the current scientific and technological knowledge, promise to be particularly informative. Most other observation series from the same century, which were made for example in Dessau, Palermo, Potsdam or Surrey cover shorter periods, are less detailed or only contain the number of spots in tabular form. “The records by Secchi and collaborators are the most detailed data on sunspots and other quiet and magnetic regions emerged into the Sun’s surface from this period, says Dr. Illaria Ermolli from INAF. “Indeed, in addition to information on the position and area of the sunspots and pores observed on the day, many drawings also include data on facular regions, spicules and prominences present on those days, and on the evolution of the observed regions. Several annotations also report on historical and natural events of the day, as e.g. hostilities in the town and observation of spectacular auroras”, adds Ermolli.

Analyzing this treasure scientifically is a huge undertaking - and not only because of the enormous size of the collection, which includes several thousands of images of the full solar disk. The sketches, which Secchi and his colleagues carefully charted on paper sheets, clearly show signs of their age: dark discolorations and smudges can be found on many sheets – and are often difficult to discern from the actual sunspots. In addition, the various observers – at least five others besides Secchi can be clearly identified – depicted the sunspots quite differently. While Secchi himself tended to indicate the sunspots in rough outlines only, some of his fellow observers showed more attention to detail (and possibly artistic talent). Using fine pencil strokes, they recorded the fine structure of each individual spot in great detail.

“Identifying all the sunspots requires a careful and, above all, human look at each drawing,” says Chatzistergos. Because of the extreme variety of the content of the solar drawings, attempts to make this task easier with the help of an automated process did not deliver satisfactory results.

Many helping eyes

As of today, more than 15,000 images with excerpts of the historical drawings are available on Zooniverse. The sections contain groups of closely adjacent and sometimes quite small sunspots. The researchers are now hoping for many sunspot detectives to help with their work. In order to obtain reliable figures, as many amateur researchers as possible must process each image section. The images will be accessible for one year.

The web portal Zooniverse offers a platform for research projects that rely on the help of lay people, so-called citizen science projects. The portal is operated by the Citizen Science Alliance, which is made up of representatives from seven renowned research and educational institutions. These institutions include the Adler Planetarium in Chicago (USA), Oxford University (England), and Johns Hopkins University (USA). The more than 90 research projects hosted by Zooniverse are extremely diverse and stem from fields such as astronomy, biology, medicine, history, and linguistics. For example, amateur researchers can count seabirds, identify individual elephants by their characteristic ear features, transcribe historical manuscripts or interpret the first speech attempts of small children. Projects in the field of astronomy and space research were among the first citizen science projects and are also strongly represented on Zooniverse.