Zooming in on the Sun

Newly analyzed data from ESA’s Solar Orbiter offer a unique view of the entire solar disk.

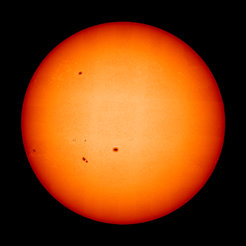

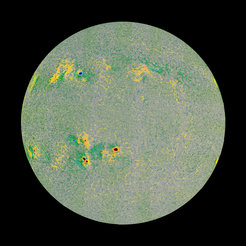

New images of the Sun’s visible surface released today show the entire solar disk in unprecedented detail. They were created by researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany from observational data obtained by Solar Orbiter’s Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) from March 22 of last year. At that time, Solar Orbiter was cruising just outside Mercury’s orbit and from there had an unobstructed view of our star. In the images, the typical features of the solar surface can be seen: the granular pattern created by ascending and descending solar plasma, dark sunspots as well as their delicately structured edges. Further images reveal the strength of the magnetic field and the direction of the plasma flows. Simultaneously captured observations of the hot corona, recorded by Solar Orbiter's Extreme-Ultraviolet Imager (EUI), make it possible to understand where and how the sometimes temperamental processes of the Sun's atmosphere occur.

No body in our Solar System is as dynamic and complex as the Sun. In order to understand as many of its caprices as possible, ESA’s Solar Orbiter is equipped with a total of six scientific instruments that look into different layers of our star. For example, EUI captures the Sun’s particularly short-wave ultraviolet radiation which originates primarily in its hot outer atmosphere, the solar corona. The double telescope PHI focuses on the visible surface below, the photosphere. The light emitted from there also contains information about the strength of the Sun's magnetic field and the velocity of the solar plasma. The images published today are derived from EUI and PHI data from March 22, 2023.

“If you want to understand the Sun in its entirety, it is essential to look into all its layers simultaneously and with high resolution,” said Prof. Dr. Sami K. Solanki, MPS Director and PHI Principal Investigator. “Solar Orbiter is capable of this like no space probe before,” he added. In addition to its extensive instrumentation, another of Solar Orbiter’s advantages is its unusual trajectory. It takes the spacecraft on long ellipses around the Sun - and thus repeatedly allows it to approach our star to less than a third of the distance between the Earth and the Sun. This corresponds to around 42 million kilometers.

On 22 March of last year, approximately 74 million kilometers separated Solar Orbiter and the Sun. At this “proximity”, the Sun is too large to fit completely into the field of view of PHI's high-resolution telescope. Instead, a total of 25 images of parts of the Sun were taken over a period of several hours, which researchers from the PHI team have now combined in a mosaic to create full-disk views.

“The information we need for our magnetic maps of the Sun, for example, is hidden in only a tiny part of the captured light,” explained MPS scientist Dr. Johann Hirzberger from the PHI team, who created the mosaics. “The data can therefore only barely be compressed on board the probe. Due to the large distance to Earth and the comparatively low data transfer rate, the huge amounts of data that are generated in this way sometimes reach us only months after the actual observations,” he added. Since Solar Orbiter continues its journey around the Sun even during the measurements, the individual images are all taken from slightly different perspectives. These effects must be carefully taken into account when piecing together the mosaics. Nevertheless, the PHI team expects to be able to provide similar high-resolution views of the entire solar disk more quickly and regularly in the future, approximately twice a year. They will help to understand how our grasp of the Sun as a whole is governed by its smallest structures and processes.

The full-disk images of the photosphere published today have a resolution of around 175 kilometers per pixel. In terms of detail, they fall short of those obtained by the most powerful solar telescopes on Earth. However, the ground-based telescopes can only image a very small section of the solar surface in high resolution. And due to the difficult observation conditions on Earth, where constant air turbulence disturbs the view, it is hardly possible to ever put these “snippets of the Sun” together to form a whole. As the Earth's atmosphere also absorbs most of the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation, simultaneous images of the corona from Earth are also not possible.

Sunspots and complex magnetic field

Zooming in on the new images of the Sun reveals the full complexity and beauty of our star. In visible light (Figure 1), a granular pattern covers the photosphere. It is an expression of the hot plasma that rises inside the Sun, cools and sinks down again - very similar to boiling water on a stove top. Sunspots, dark areas on the solar surface, can also be seen. As PHI's magnetic map, the magnetogram (Figure 2), shows, the Sun's magnetic field is particularly strong in these areas. It prevents hot plasma from rising from the depths. In the area of the sunspots, the solar surface is therefore cooler and appears darker. The different colors in the magnetogram represent the strength and direction of the magnetic field. The strongest fields are shown in red (pointing outwards) and blue (pointing inwards).

The velocity map, the tachogram (Figure 3), illustrates the speed and direction of the plasma flows on the solar surface. The map primarily shows how the plasma rotates with the Sun, but also reveals smaller-scale movements near the sunspots. Blue shows the movements in the direction of the space probe, while red shows the movements away from the space probe.

The EUI image (Figure 4) gives an impression of the dynamic processes in the corona. The hot plasma there flows along closed magnetic field lines, often from sunspot to sunspot, or escapes into space along outward-pointing field lines.